This is another in a series of entries focused on the costs of inaction – what we will pay if climate change continues unchecked.

In a previous installment, we introduced integrated assessment modeling as one approach economists take to answer the question: how much will we pay if climate change continues unabated? Today we’ll explore an alternative, bottom-up approach.

A bottom-up approach provides a detailed accounting of climate damages in specific sectors, building upwards from historical data. These bottom-up studies have the advantage of being less dependent on modeling assumptions. The disadvantage is that sectoral estimates cannot be added up to represent the cumulative impact of climate change on the economy of a country or a region.

This approach is used in case studies of the impacts of climate damages on specific sectors of the economy or on states or regions. While it cannot provide a complete picture of the costs of inaction, it can produce compelling snapshots of the magnitude of potential damages from climate change. Preventative measures to limit warming may be justified on the basis of these snapshots alone.

Bottom-up analyses usually assume that the baseline for comparison is a “business-as-usual” approach to climate change in which emissions continue to grow and no efforts are taken to mitigate emissions or to adapt to the impacts of warming. Assumptions about changes in sea-levels, precipitation patterns, temperature increases, agricultural productivity, and the like are typically based on reputable and widely cited emissions and climate scenarios presented by the UN IPCC and/or the US Global Change Research Program (US GCRP).

Below we present a sampling of just some of the best available estimates of the costs of climate change for US sectors. We rely mostly on a widely cited 2008 study by Frank Ackerman and Elizabeth Stanton on the impacts of climate change for US energy supplies, water systems, real estate and infrastructure.

Impacts on Energy Supplies

While it is commonly understood that our reliance on fossil fuel energy drives climate change, the potential impacts of climate change on energy supplies in the US is far less appreciated. Rising temperatures may mean lower heating demands in northern states, but demands for air conditioning and refrigeration should swell across the country. Households will be spending more to cool their homes, and will be buying air conditioning units and systems where none had ever been needed before.

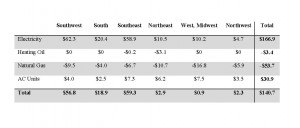

Increase in Annual Energy Costs by 2100 (billions of 2006 dollars)

Ackerman and Stanton (2008) estimate that by 2100, under a business-as-usual emissions scenario, climate change will increase total annual energy costs across the country by $167 billion, and increase annual air conditioning purchases by $31 billion, as compared to 2005. Expenditures on heating oil and natural gas will decline by $57 billion over the same period, due to milder temperatures in northern states. The net increase in energy costs across the country by 2100 will be $140.7 billion. Southeast and southwest states in the US will be hardest hit by the increases in energy costs from climate change.

Increase in Annual Energy Costs by 2100 ($ billions) - Ackerman and Stanton 2008

At the same time, higher temperatures and drought conditions could impact the efficiency of power transmission and generation systems. Water is an essential input in almost all coal and nuclear plants and in many natural gas plants across the country. When water is in short supply, power plants have little alternative but to reduce generation. Heat waves also reduce the efficiency of power transmissions at times of peak demand, resulting in costly power outages.

Droughts will also limit the amount of energy that can be produced by hydroelectric dams. US hydroelectric production can fluctuate by as much as 35% from year to year due to variations in precipitation. According to Ackerman and Stanton, severe drought in the Southeast in 2007 reduced hydroelectric production by 15% nationwide and by 45% for the Southeastern states.

Impacts on Water Supplies

Climate change will impact the nation’s water supplies, with wide-reaching potential consequences for agriculture, human health, tourism, transportation, and energy production. Ackerman and Stanton (2008) estimated that water costs in the US could rise by $950 billion per year by 2100. This is likely a low, conservative estimate of what the water related costs of climate change may be. This estimate is based on annual water demand and supply and ignores seasonal fluctuations. Moreover, this estimate is based only on water supplies and does not account for the damages from precipitation extremes, such as droughts or floods. Nor does it include the effects of changed water supplies on agriculture, especially in irrigation dependent areas in the west and northwest.

Impacts on Real Estate, Infrastructure, and Transportation

Recent experience with Hurricane Katrina, which cost an estimated $200 billion, reveals the vulnerability of US coastal populations and infrastructure to extreme weather, sea level rise and flooding due to climate change.

Ackerman and Stanton (2008) estimate that the damages to the US from hurricanes could reach $422 billion annually by 2100. They estimate the annual loss from sea-level rise in the US at $360 billion per year by 2100. Combined, the annual losses from increased storm damage and sea-level rise by 2100 are $782 billion dollars, or almost 1% of US GDP each year.

These estimates are likely conservative estimates of the impacts of sea level rise and hurricanes, because they do not consider all of the indirect ways in which flooding, storms, and sea level rise can impact economic output. For example, transportation systems in the US are highly weather dependent and extreme weather events can cause costly disruptions. Droughts can impede river traffic. According to some estimates, reduced water levels in the Mississippi during a severe drought in 1988 cost the region $49 billion when commercial shipping had to be replaced with more expensive rail transport. The US GCRP reports that in the Gulf Coast region, 64% of the interstate highways, 57% of the arterial roadways, roughly half of the rail miles, 29 airports, and almost all ports are below 23 feet in elevation and are at risk of extensive damage from hurricanes, storm surge, and long-term sea-level rise from climate change.